If Your Construction Tech Failed, This Might Be Why

Your implementation failed. Now you’re left wondering why.

And while it might be easy to point fingers at the tech, or at the executive sponsor or even at the construction industry in general for not understanding how to best move forward, there just might be a different reason things went sideways.

More often than not, the effort required to make technology work peaks before the ROI becomes visible. Somewhere in that gap, many simply give up.

Over the years I’ve traversed this route more times over the years than I care to admit. We ran into it at Kiewit (several times), later at Google (they might still be there) and many more times over on the vendor side throughout the last decade.

Different organizations. Different mandates. Different tools. But the same lull in optimism.

The first time you experience it, you assume something has gone wrong. You question the decision, the timing or even yourself. But the more reps you take, the more you begin to recognize what it actually is: a phase. A predictable, human response to meaningful change that we must power through.

But there’s a second side to this equation, and it wasn’t until recently that I put two and two together.

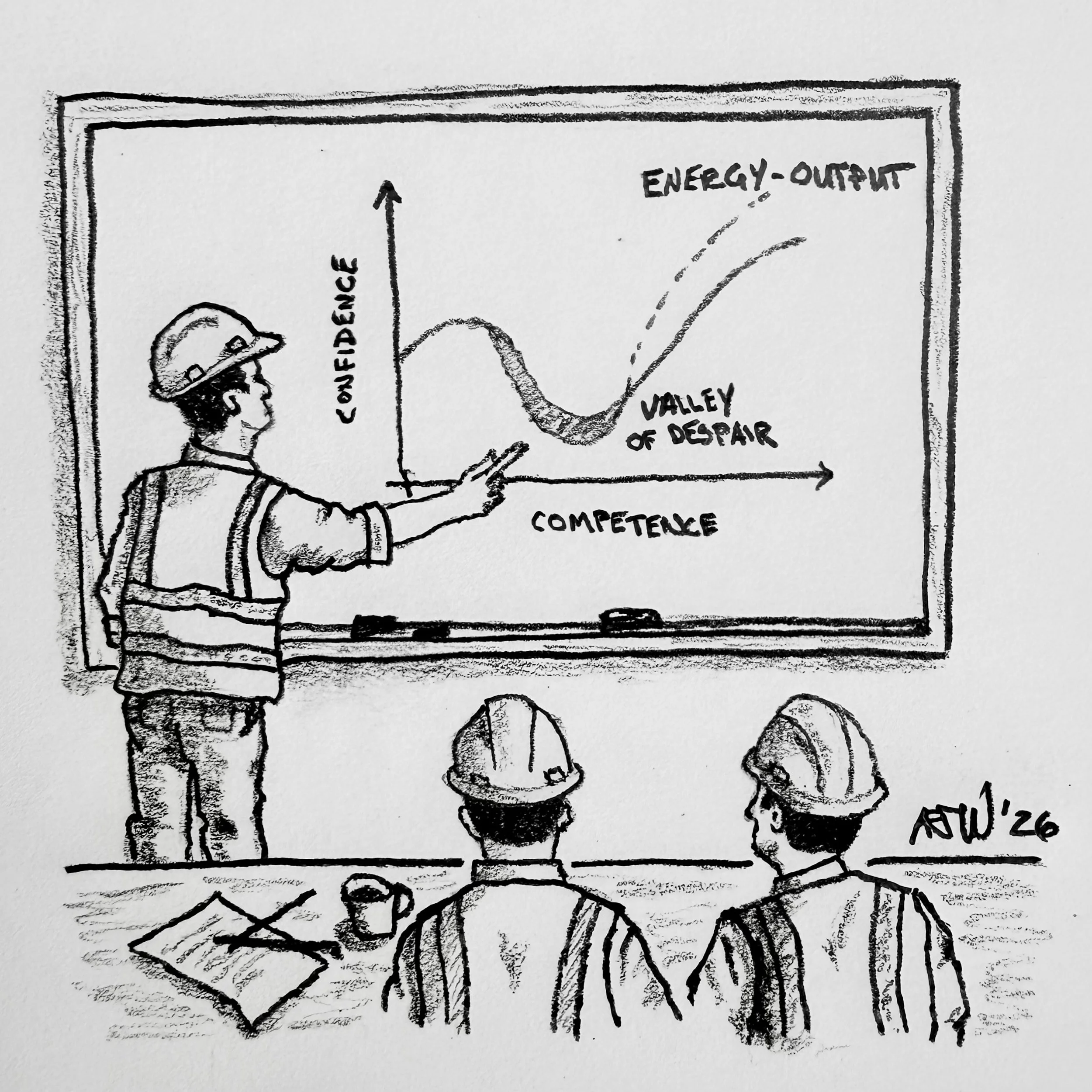

The Energy-Output Curve

Sahil Bloom shared an idea he calls the Energy-Output Curve, and the more I sat with it, the more it mirrored experiences I’d lived through but never quite articulated. The premise challenges a deeply ingrained assumption most of us carry, especially in construction. We expect effort and results to move together. More energy in should mean more output out. Linear. Predictable. Fair.

But that’s not how complex work actually behaves.

At the beginning of any new initiative, small amounts of effort tend to produce outsized results. Momentum comes easily. Progress is visible. Feedback is quick. This is the phase where optimism thrives, because it feels like the system is working with you instead of against you.

Then the curve flattens. The same amount of effort doesn’t produce the same results anymore. Energy continues to go in, but the output slows. The work gets harder, the feedback loop stretches and the wins become harder to spot (sound familiar?). Most people interpret this moment as failure, when in reality it’s the most demanding part of the journey.

Because if you persist, something else happens. The system begins to compound. The work you’ve invested finally connects. Small additional effort produces disproportionate gains, not because the work suddenly got easier, but because the foundation is finally strong enough to support it.

As I read Sahil’s explanation, I realized I knew this curve intimately. We just call it something else in construction technology.

Insert The Valley of Despair

In the world of technology implementation, that similar flattening of the curve has a name: the Valley of Despair.

Anyone who has ever implemented a new platform, process or operating model recognizes it immediately. The rollout starts with confidence. The demos are compelling. The vision is clear. Everyone believes this new tool will finally solve the problems that have lingered for years.

Then reality shows up.

Training takes longer than expected. Data is messier than promised. Processes feel slower before they feel better. The tool that was supposed to simplify work suddenly feels like it’s adding friction. Confidence dips, frustration rises and all of a sudden people are questioning whether the old way was actually that bad after all.

This is the point where many organizations stall. Not because the technology is broken, but because the emotional cost of change becomes visible all at once. The Valley of Despair isn’t a surprise. It’s a pattern.

So why do we keep treating it like an anomaly instead of a predictable phase?

What’s Really Happening in the Valley

The Valley of Despair isn’t about technology. It’s about people.

It’s the space where old habits no longer serve you and new habits haven’t fully formed yet. It’s where competence temporarily drops before it rises again. And for people who take pride in knowing their craft, this moment can feel deeply uncomfortable.

In construction, this discomfort is amplified. This industry values experience, efficiency and mastery. So, when a system makes someone feel slower or less capable, even temporarily, it’s easy to label their negative response as resistance. In reality, it’s often something far more human. It’s fear of losing mastery. Fear of looking inexperienced. Fear of being accountable in a new way.

That’s why the valley feels so deep. It’s not just operational. It’s personal.

When the Curves Snap Together

But what I realized recently is when you overlay the Energy-Output Curve on the Valley of Despair, the picture becomes remarkably clear.

The early optimism of a technology rollout aligns perfectly with the activation phase of the energy curve. Small effort creates visible momentum, and belief does a lot of the heavy lifting. As the work deepens, the organization enters the diminishing returns zone. Energy input peaks here. Training, configuration, data cleanup, process redesign and change management all demand sustained effort at the same time visible progress slows.

And that’s where most teams quit.

Not because the technology doesn’t work. Not because the decision was wrong. But because the curve temporarily lies to them and makes progress feel like failure.

But the teams that make it through? They experience a clear inflection point. Workflows stabilize. Data becomes trustworthy. People stop thinking about the tool itself and start thinking with it. Nothing magical changes in the software, but rather what changes is that the organization crosses the energy threshold where compounding finally begins.

The Insight We Rarely Admit

Most technology failures aren’t technical. They’re energy failures.

Organizations abandon transformations at the exact moment the work becomes hardest and the payoff feels most distant. Discomfort gets misinterpreted as dysfunction and this valley gets treated like the final verdict instead of a checkpoint.

But what we must understand is that the Valley of Despair is not a signal to turn back. It’s confirmation that the organization is doing the most important work of the transformation right this moment.

Teams that expect the valley will plan for it.

Teams that plan for it will resource it accordingly.

Teams that resource it accordingly will eventually cross it.

Meanwhile, teams who don’t label the effort a failure and move on, often to repeat the same cycle with their next transformation.

Why Does This Matter in Construction?

Construction doesn’t lack innovation. It lacks follow-through.

The industry is full of half-finished transformations and tools that never reached their potential. Most of those stories didn’t end poorly because the technology was flawed. They ended because leaders underestimated the energy required to guide people through the middle.

Construction technology isn’t one-size-fits-all or plug-and-play. It’s design-and-adapt. It requires leadership that stays present after the kickoff meeting, clarity that extends beyond the contract and permission for teams to feel uncomfortable before they feel confident.

When leaders can stand in the valley and say, “This is expected. Stay with me,” the outcome changes. Not instantly, and not effortlessly, but meaningfully and permanently.

Rise to the Moment

Every meaningful transformation has a moment where regret feels stronger than progress. That doesn’t mean the decision was wrong. It means the organization is early in the compounding phase.

The Valley of Despair is the point where energy investment peaks before output compounds. Teams that plan for it cross it. Teams that don’t call it failure.

I’ve crossed that valley more than once, and I know I’ll cross it again. Because on the other side isn’t just better technology. It’s stronger systems, more resilient teams and work that finally delivers on its promise.

Construction is hard. Change is harder.

But the view from the far side of the valley is worth the climb.

Construction is cool, tell your friends!